On May 30, the new Senate was elected. But what does the Senate actually do? What is its place in our state system? What is its power and influence on government policy? And how will the Rutte IV Cabinet push its legislative agenda to majorities in both the House of Representatives and the Senate?

Our parliamentary bicameral system

Our Dutch parliamentary system has rested on a two-chamber system at the national level since 1815. Political primacy rests with the House of Representatives, which consists of 150 directly elected full-time members. The task of the Lower House is threefold: representing the people, co-legislating and controlling.

The Senate consists of 75 members, elected in stages. The task of the Senate is twofold: co-legislative and controlling. Membership is not full-time. The Senate in plenary session usually meets only on Tuesdays.

Senate elections

The term of the Senate is four years. The stepped elections are held in the month of May following the Provincial Council elections. It is the newly elected States that are eligible to vote for the Senate. In 2017, this was expanded to include members of electoral colleges of the Caribbean Netherlands and Dutch nationals living abroad.

The allocation of seats is complex. Votes cast are assigned a vote value. Thus, a vote of a member of parliament from densely populated South Holland counts more than a vote from sparsely populated Zeeland.

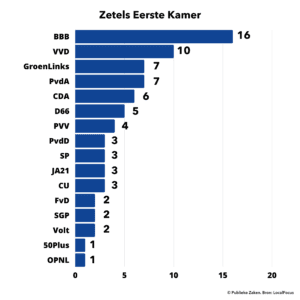

The distribution of residual seats can and is influenced by parties by making agreements among themselves. Parties with a surplus of votes can ask Statesmen to cast their vote for another party to help that party gain a residual seat. Through tactical voting, the parties forming the coalition in the House of Representatives managed to shift two residual seats from BBB and PVV to CDA and CU. Mistakes or disloyalty to one's own party can also lead to seat shifts. This year, due to a vote by a dissident South Holland Statesman, GroenLinks losta seat in favor of Volt, doubling its seat count to two. In 2011, a Statenlid colored the box on the ballot with a ballpoint pen blue instead of the prescribed red. That cost D66 a seat at the time.

The political significance of the result

New legislation only comes about if it is supported by a majority in both Houses. In the Lower House, the government can usually count on support from the coalition parties VVD, D66, CDA and CU. They have a majority of 77 seats there. In their coalition agreement, they have enshrined the main points of policy and a legislative agenda.

A coalition majority in the Senate is always uncertain. First, the groups in the Senate are not bound by a coalition agreement. Moreover, the coalition did not and does not have a majority in the Senate. Indeed, the coalition parties' seat count has dropped from 32 to 24 seats. As many as 14 additional votes are needed to reach the minimum majority of 38 seats. This presents the government with headaches and uncertainty about obtaining majority support for bills. Not for the first time. Ever since 2010, successive cabinets have lacked coalition majorities in the Senate.

The Senate as a 'chambre de reflection'

The task and role of the Senate differs substantially from that of the House of Representatives. Because the Upper House is not directly elected by citizens, the people's representative role is not predominant. In it, the Senate respects the political primacy of the Lower House. In the Lower House, the emphasis of MPs and political groups is very much on interpreting ideas and feelings of the part of the electorate being represented. In the debates, the verbal intercourse is usually dominated not by the search for common ground, but by the magnification of differences. Oppositions between opposition and coalition are sharply marked and ministers are sharply and in detail monitored and questioned by the opposition.

The Senate is less driven by day-to-day politics. Although it, like the Lower House, has a monitoring task, it focuses primarily on the quality of legislation, such as the aspects of efficiency and feasibility.

The Senate is also reticent in its budget rights. The primacy of the directly elected House of Representatives over the distribution of state resources is also respected here.

The Senate lacks the right of amendment. It cannot amend bills, only accept or reject them. The Senate is also reluctant to use other instruments. The right of inquiry and holding the government accountable with the right of interpellation is used only sporadically. Political statements in the form of motions are made, but far fewer in number than in the House of Representatives.

How does the power of the Senate manifest itself?

Despite its relatively limited constitutional set of instruments and its more restrained view of duties and roles, the Senate nevertheless has a great deal of power and influence, which manifests itself subtly and very effectively. Not by frequently rejecting bills, but by eliciting commitments from ministers. Also by demanding from ministers precise explanations of how legislative provisions should be seen and read, the Senate exercises its influence. After all, the judiciary involves the legislature in the application of the law in case law.

The Senate has no power to amend the bill, but may "invite" ministers to present what is known as a novella: a bill to improve or supplement the submitted law.

The more independent position of members and groups of the Senate means less partisan discipline, more independent deliberations and a more subtle way of influencing. How that works is well explained in this article in which Senate member Koole accounts for how the PvdA faction in the Senate ultimately did support the ratification of the international trade treaty CETA in contrast to the faction in the House of Representatives.

The handling of the Nitrogen Emergency Act is another good example of how the government succeeded in securing a majority for a politically sensitive bill, by gaining support in the Senate, in addition to the coalition, from the SGP, SP and Group Otten groups.

The impact of the 2023 elections on the Rutte IV administration's political agenda

Even before the Upper House elections, the shadows of shifting political proportions were casting ahead. The BBB, with 16 seats, has become by far the largest group, demanding more influence and say in government policy. Not only when it comes to dealing with the nitrogen issue, which was at stake in the election. The demand, not granted, to adjourn the vote on the Future of Pensions Act, pending the installation of the new Senate, also testifies to this.

On the other side of the political spectrum, the so-called "left cloud" is also stirring. Although the combination of the Green Left and the Labour Party lost one seat overall, it forms a joint group of 14 members that has gained political relevance.

It is virtually impossible for the government to secure a majority of at least 38 seats in the Senate without either the BBB or the GroenLinks/PvdA combo. This could lead to deadlocks. A bill to deal with nitrogen that goes far too far for the BBB but not far enough for GroenLinks/PvdA is virtually impossible to get through the Senate.

Changing the balancing scheme for electricity generated by solar panels requires an amendment to the Electricity Act, which GreenLeft/PvdA did not support in the Lower House. The BBB's website distances itself from this bill in strong words.

High demands are being made on the maneuvering skills of Prime Minister Rutte and the members of his government in the remaining reign. Lavering in the turbulent political waves, cliffs must be circumnavigated both to port and starboard.